Synthetic Speed Tonguing

By

Clark W Fobes – Copyright 2000

Certainly one of the most difficult aspects of clarinet playing is articulation. Volumes can (and have been!) written regarding the mechanics of proper tongue position, proper air and voicing. However, this article is directed to the advanced player who possesses a relatively high level of technical mastery in regard to articulation. My interest is in describing a new system of tonguing that will facilitate repeated articulation at fast tempi. This method is a synthesis of single tonguing and double tonguing techniques. I have successfully applied this technique to my playing over the past year and have used it in performance repeatedly. My colleagues cannot discern when I am using it and when I am not. I believe that anyone can learn this technique and hope that it opens a new vista of technical and musical possibilities for those of us who do not possess a "snake" tongue.

Most clarinetists who have achieved a high level of technical execution understand the mechanics of tonguing and know how to practice to develop rapid articulation. However, it is clear to me as a student of the clarinet for almost forty years and from discussing the subject of rapid articulation with many excellent players, that we all have a physical limitation as to the ultimate speed we can achieve. I am blessed with a faster than average tongue, but I don’t have the ability to single tongue "The Bartered Bride" at 144-152 or the famous "Mendelssohn Scherzo" at 90. In fact, I would offer that these tempi are out of range of the majority of players. So what do we do as performers when confronted with a fast passage that is intended to be articulated and is beyond the limits of our tonguing ability? Learning to double tongue appeared to me as a viable alternative to the old "slur-two, tongue-two" surrender.

I began experimenting with double tonguing about ten years ago. It was frustrating to discover that very few clarinetists knew how to double tongue and even fewer knew how to describe what they were doing. Robert Spring (Professor of Clarinet, Arizona State University) is probably the most renowned practitioner of clarinet double tonguing. Mr. Spring wrote a brief article on the mechanics of multiple articulation in "The Clarinet" Vol. 17 no.1 (Nov – Dec 1989). I used his article as a reference point, but I was otherwise on my own. It was not until 1998 that I began seriously practicing double tonguing and worked at developing a true fluency.

As I gained confidence in my double-tonguing I began to use it in performance. However, I soon discovered that double tonguing had a few serious drawbacks. One, I could not emulate a good staccato and two, prolonged practicing caused a change in my tongue position that altered my throat cavity. The result was a loss of focus in my sound and a tendency to play flat. I was able to play sixteenth notes at 170 to the beat, but I certainly did not like the sound. Also, most often I did not need to double tongue an entire passage, but I could not switch from single tongue to double tongue mode easily. As I practiced various excerpts it was also apparent that continuos double tonguing did not suit all metric or musical inflections.

I first stumbled on the idea of combining double tonguing with single tonguing when attempting to apply double tonguing to the "Scherzo" from Mendelssohn’s "Midsummer Night’s Dream".

The first groups of sixteenth notes do not need to be double tongued and in fact lose the separation of a good staccato when played that way. The first problem for most of us comes with bars 7 and 8. Here we have ten notes in succession, all tongued. Generally, the last three or four notes begin to sound labored as the tongue tenses. I attempted to double tongue this in the standard fashion of repetitive " t-k, t-k", but the coordination was awkward in this metric context. In order to practice without tension, I would often slur the first two notes of bar 8. It occurred to me that an insertion of a "t-k" unit instead of a slur would have the same effect of resting the tongue. Voila! It did not take me long to learn how to insert this so that it sounded quite adroit. (In this excerpt and all other examples, the "t-k" unit is marked with a bracket)

Further in the passage at bars 15 and 16 is a string of twelve notes in succession. Following the same principal, I applied the double tongue as indicated.

There are several advantages to this method. Only two notes of the twelve are articulated with a "k" and the energy of the tongue in these two places enhances the rhythmic underpinning. Also the tongue is relaxed in the ascent to "C". With relaxation one can make a feathery decrescendo which sounds very musical and virtuosic. I can easily play this excerpt at 92 and 94 is not out of range (although I think it sounds like a cartoon at that speed!) I will give a few more examples of excerpts after a thorough discussion of the basics and a method for practicing double tonguing and "Synthetic Speed Tonguing".

My method is a synthesis of double tonguing and single tonguing techniques, so you must learn how to double-tongue before you can proceed and you must have a reasonable amount of skill at rapid single tonguing. As I stated previously, this article is not meant to be a dissertation on the mechanics of articulation. The following section regarding double tonguing is not a definitive discourse, but will point in you in the proper direction for developing a concept of double tonguing as an adjunct to "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". I suggest focusing your attention on my method of speed tonguing as soon as you can incorporate double tonguing into your study. For further information on double tonguing you may wish to read Robert Spring’s article mentioned earlier.

In order to approach your study with the most success you must use a metronome. The best possible method is to use a metronome that will produce subdivisions to each pulse. I use a "DR BEAT" metronome. Hearing each subdivision (usually sixteenth pulses) as you practice will greatly enhance your ability to articulate evenly

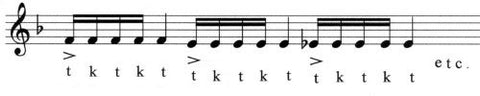

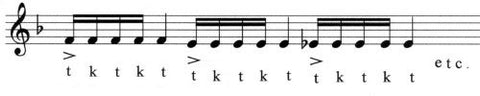

Below is the standard pattern for double tonguing where "t" represents the tongue meeting the reed and "k" represents the back of the tongue against the palate.

Roger Stevens in his fine book Artistic Flute: Technique and Study describes his concepts of "compound articulation" (double tonguing or triple tonguing) in a very concise manner. He makes several good points that I would like to quote.

Roger Stevens in his fine book Artistic Flute: Technique and Study describes his concepts of "compound articulation" (double tonguing or triple tonguing) in a very concise manner. He makes several good points that I would like to quote.

"In all manners of articulation the tongue may be best considered as performing the function of a valve, not as the initiator of the expulsion of air".(For single reed players this applies to the "k" stroke only. –CF)

"To make the two articulated sounds as similar as possible, the following suggestions must be followed. The vowel used with the "T" and the "K" must be the same, i.e., the "T" and the "K" must rhyme. Tone quality can be affected by changing the position of the tongue in the mouth, the same manner in which vowels are altered in speech."

"The point of articulation for the "K" must be as far forward in the mouth as is comfortably possible …. In developing the "K" attack, care must be taken to insure that the throat muscles, especially those which are involved in swallowing, are not activated at the same time the tongue is forming the "K". When this happens, the airstream is stopped not only at the "K" point, but also back in the throat. The result is one of over-riding the action of the tongue when time for the attack, and the attack will then tend to be soggy, mushy, even late."

Of course many of the problems associated with tonguing are much different for the clarinet, but Mr. Stevens makes relevant points about matching the quality of "T" and "K" when using compound tonguing and a very important point about sympathetic throat movement when producing the "K" stroke.

Apropos to Mr. Stevens’ comments, I use the consonant "t" and "k" for double tonguing. The "t" placement is the normal position for starting a tone. I use the tip of the tongue to the tip of the reed. This places the tongue in a natural position that allows the back of the tongue to touch the soft palate easily when using the "k" stroke. The vowel that produces the best results for me is "oo". Thus I think of "too" and "koo" which positions the tongue comfortably forward and is a vowel conducive to good clarinet tone.

Robert Spring uses "TEE-KEE" in order to keep the tongue high enough to produce the "k" articulation in the upper register. I have tried this, but for my taste, the sound is too thin. Also, I cannot produce the "EE" position with out a sympathetic pulling at the corners of my mouth. My concept of embouchure has always been to keep the lips "forward" and form an "oo" shape when playing. However, I do find when double-tonguing higher than "G" above the staff that a slight raising of the tongue facilitates this register.

Spring also suggests beginning the study of multiple tonguing with the mouthpiece and barrel only. I found that starting with the throat tones and a slightly softer than normal reed was also effective. He also indicates beginning at a tempo of no less than 112 with a sixteenth note subdivision. I agree that it is important to move to faster tempi early in your learning. The "k" is produced in a lighter fashion this way, but initial slow playing will help with a thorough understanding of the tongue motion and placement.

Begin with throat "E" or "F" and just try "k-k-k-k" etc. for several beats. The sound of the "k" will probably be awful when you first start - not to worry. Focus on keeping the stroke forward on the palate.

Set the metronome to 72 and using only the "k" stroke see if you can place a "k" on every beat. As you get better at this increase the metronome speed and try to lighten up the articulation. The "k" need only be a slight interruption of the air stream – similar to the slight interruption made by the tip of the tongue to the tip of the reed. You won’t master this in a few sessions, but you will become fluent enough after a few days to add the "t".

Return to a moderate tempo on the metronome (72-80). Play two eighth notes on each pulse, but as you play alternate "t" and "k".

It may not be pretty, but you are double tonguing! You will have to experiment with the "k" stroke to understand how to keep the stroke light, but also make a clear start to the tone. Try to move the metronome speed up quickly. Learning how to "speed through" the "k" forces you to be efficient with that motion. Once you are able to play repeated eighth notes at about 200 it is time to move to sixteenth note patterns.

It may not be pretty, but you are double tonguing! You will have to experiment with the "k" stroke to understand how to keep the stroke light, but also make a clear start to the tone. Try to move the metronome speed up quickly. Learning how to "speed through" the "k" forces you to be efficient with that motion. Once you are able to play repeated eighth notes at about 200 it is time to move to sixteenth note patterns.

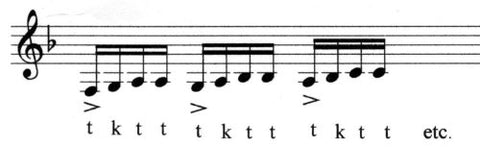

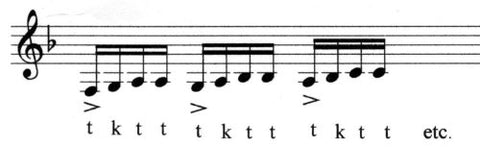

Return to a moderate tempo (72 or slower) and play the following simple pattern.

Notice that I have added an accent to the beginning of each group. It is immensely helpful to think of "t-k" as a unit. The slight burst of energy associated with the accent also adds air speed to support the "k" portion of the stroke. This exercise will also help you in learning how to bring the tongue back to the tip of the reed quickly after the "k" stroke. Practice this pattern for several days. You may want to start expanding your range downwards just to avoid boredom and to discover how varying resistance impacts the "k" stroke. When you can play the above pattern evenly at a moderate tempo of 100 try this pattern:

Notice that I have added an accent to the beginning of each group. It is immensely helpful to think of "t-k" as a unit. The slight burst of energy associated with the accent also adds air speed to support the "k" portion of the stroke. This exercise will also help you in learning how to bring the tongue back to the tip of the reed quickly after the "k" stroke. Practice this pattern for several days. You may want to start expanding your range downwards just to avoid boredom and to discover how varying resistance impacts the "k" stroke. When you can play the above pattern evenly at a moderate tempo of 100 try this pattern:

Try to develop some speed with these short groups

Try to develop some speed with these short groups

Once you become comfortable with this, add successive groups of sixteenths to increase endurance. Return the metronome to a moderate tempo.

And then:

And then:

Expand the range downward with this pattern:

Expand the range downward with this pattern:

Once you become relatively fluent in the chalumeau register you should expand your range upward. Use the above pattern and work chromatically upwards from throat "F". You will encounter varying resistance with each note. As you go higher you will begin to encounter a limit. I believe most people can play fairly comfortably up to "G" above the staff, but above that is difficult. (This is where a slight raising of the tongue toward an "ee" vowel will help.)

Once you become relatively fluent in the chalumeau register you should expand your range upward. Use the above pattern and work chromatically upwards from throat "F". You will encounter varying resistance with each note. As you go higher you will begin to encounter a limit. I believe most people can play fairly comfortably up to "G" above the staff, but above that is difficult. (This is where a slight raising of the tongue toward an "ee" vowel will help.)

The final step for our purposes is to incorporate double tonguing with changing notes. This is the most difficult aspect of double tonguing and will take some time to master. The following pattern was the most useful for me in coordinating my fingers and tongue. This is also an excellent exercise for speeding up the "k" stroke. You can get inventive with this and play it through all of the keys and also apply it to the chromatic scale. Play it upwards and downwards.

This is a good beginning to learning double tonguing, but this is where I will part company with the double tonguing discussion. With this basic knowledge of double- tonguing I believe one can incorporate it is as component of "Synthetic Speed Tonguing" and continue to improve the "k" motion.

This is a good beginning to learning double tonguing, but this is where I will part company with the double tonguing discussion. With this basic knowledge of double- tonguing I believe one can incorporate it is as component of "Synthetic Speed Tonguing" and continue to improve the "k" motion.

To begin, let us return to the following simple pattern, but use the "k" stroke on the second note only. This is the basic pattern for "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". All uses are either a repetition or a minor variation of this pattern. I rarely place a "t-k" unit in a position other than at the beginning of a beat.

This is the basic pattern for "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". All uses are either a repetition or a minor variation of this pattern. I rarely place a "t-k" unit in a position other than at the beginning of a beat.

Notice again that I have added an accent to the beginning of the group. I find that starting from a rest is the most difficult aspect of using "t-k" units. The added support of air and the energy of the attack will help your start. As you develop this method you can drop the accent and think of "energized" air to support your starts. Play through all of the variations described in the section on double tonguing, but substitute the above pattern.

For example: etc.

And:

etc.

And:

It may take several weeks or months to develop your "k" stroke, but as you become more facile it is important to move ahead and begin to incorporate the method into moving notes.

It may take several weeks or months to develop your "k" stroke, but as you become more facile it is important to move ahead and begin to incorporate the method into moving notes.

You already know this pattern: Now try this variation which will orient you to the basic pattern:

Now try this variation which will orient you to the basic pattern:

Be inventive and develop patterns for short "burst" tonguing including chromatic neighbors. This will help develop your speed as well.

Be inventive and develop patterns for short "burst" tonguing including chromatic neighbors. This will help develop your speed as well.

Now it is time for the real thing, scale studies. The fundamental premise for my method is that the "t-k" unit can be substituted anywhere one would normally place a two-unit slur to accommodate a passage that is too fast to single-tongued in its entirety. Begin by playing only these short patterns:

Play once with the "slur-two, tongue-two" pattern and then repeat in tempo without the slurs. Play through all keys starting on Low F. Your final short scale will start on "F" at the top of the staff. This is a good workout and will take you through some awkward passages.

Play once with the "slur-two, tongue-two" pattern and then repeat in tempo without the slurs. Play through all keys starting on Low F. Your final short scale will start on "F" at the top of the staff. This is a good workout and will take you through some awkward passages.

Now you can extend this pattern to full scale practice. I use the following two patterns as part of my warm up routine. I play them through all keys from low "F" to "C" in the staff. If I have time I play at three tempi, 136, 144, 152. On good days I try to bump the last number up a few notches.

And then in tempo:

And then in tempo:

The initial playing of the "slur two, tongue two" pattern sets the finger motion and reinforces the tongue position for all of the "t" articulations. It is important to use the same "t" stroke when playing the synthesized pattern. As I play through my scales I focus my attention on the sound and quality of the "t" stroke. The "k" is simply part of the "t-k" unit and should not affect the quality of the other strokes. Try to match the quality of the inception of the "k" to the "t" stroke. Avoid playing too legato initially. The difficulty is in making the "k" hard enough to sound clear, but not labored.

The initial playing of the "slur two, tongue two" pattern sets the finger motion and reinforces the tongue position for all of the "t" articulations. It is important to use the same "t" stroke when playing the synthesized pattern. As I play through my scales I focus my attention on the sound and quality of the "t" stroke. The "k" is simply part of the "t-k" unit and should not affect the quality of the other strokes. Try to match the quality of the inception of the "k" to the "t" stroke. Avoid playing too legato initially. The difficulty is in making the "k" hard enough to sound clear, but not labored.

Once you have learned the basic concept, you can apply this method to any number of exercises. I routinely play a chromatic scale from lowest E to C above the staff and back down following the same pattern I apply to my scales. To incorporate the pattern into 3/8 or 6/8 patterns I use the "t-k" unit on the first two notes only of a six-unit group. (See example below) The scales in the beginning of Langenus Book III are in 6/8 and can be practiced in this manner.

Very rarely I might use the "t-k" in a different position other than on the pulse. I find it easiest to place the "t-k" unit on the beat as a rule. This lends consistency to your approach and you can "switch" the "t-k" on and off as naturally as adding a slur.

Very rarely I might use the "t-k" in a different position other than on the pulse. I find it easiest to place the "t-k" unit on the beat as a rule. This lends consistency to your approach and you can "switch" the "t-k" on and off as naturally as adding a slur.

As you move the metronome up, you will find that your upper limit for speed tonguing is the same as with your "slur-two, tongue-two" model. I cannot play as fast with the synthetic method as with a pure double tongue method, but I find the artistic and musical results to be much more satisfying.

Beethoven, Symphony No. 4 – fourth movement. MM= 136 - 152

Smetena, "The Bartered Bride" – Overture. MM= 144-152

Note that at the beginning of the second system of the "Bartered Bride" I have placed a slur over the "D-B" pair of notes. It is rather difficult to start the "t-k" from this register. If the second note is clipped it will sound tongued at that tempo.

Sibelius, Symphony No. 1 – third movement

This is a good example of usage in a triple meter. Notice that the pick up notes into bar 5 of the excerpt are single tongued. This is also the case for any of the four note groups that start after a rest on the downbeat. The "t-k" unit on the primary beat helps reinforce the rhythmic underpinning of the music. Most of the notes are played with a crisp staccato that would not be possible of the entire passage was played with double tongue.

This is a good example of usage in a triple meter. Notice that the pick up notes into bar 5 of the excerpt are single tongued. This is also the case for any of the four note groups that start after a rest on the downbeat. The "t-k" unit on the primary beat helps reinforce the rhythmic underpinning of the music. Most of the notes are played with a crisp staccato that would not be possible of the entire passage was played with double tongue.

Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 3 – Second movement MM = 126 - 140

Here is another case where the ability to shift from single tonguing to a brief insertion of a "t-k" unit is possible with "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". The predominant use of the "t" renders a beautiful light quality, yet the tongue remains relaxed because of the occasional use of a "k" articulation. I do not place a "t-k" unit on the first pair of notes beginning the third system. A skip of this width from the upper register is difficult and at this point the tongue is still relaxed. I insert the "t-k" units on the next three beats only. It is difficult to play these excerpts lightly (pp) and maintain rhythmic clarity. The slight pulsing of the energized "t-k" units solves this problem.

These are only a few examples for the use of "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". There are many, many possibilities and variations and once this technique becomes a part of one’s technical vocabulary the imagination is the only limiting factor as to its applications.

Clark W Fobes

San Francisco

October, 2000

Clark W Fobes – Copyright 2000

Certainly one of the most difficult aspects of clarinet playing is articulation. Volumes can (and have been!) written regarding the mechanics of proper tongue position, proper air and voicing. However, this article is directed to the advanced player who possesses a relatively high level of technical mastery in regard to articulation. My interest is in describing a new system of tonguing that will facilitate repeated articulation at fast tempi. This method is a synthesis of single tonguing and double tonguing techniques. I have successfully applied this technique to my playing over the past year and have used it in performance repeatedly. My colleagues cannot discern when I am using it and when I am not. I believe that anyone can learn this technique and hope that it opens a new vista of technical and musical possibilities for those of us who do not possess a "snake" tongue.

Most clarinetists who have achieved a high level of technical execution understand the mechanics of tonguing and know how to practice to develop rapid articulation. However, it is clear to me as a student of the clarinet for almost forty years and from discussing the subject of rapid articulation with many excellent players, that we all have a physical limitation as to the ultimate speed we can achieve. I am blessed with a faster than average tongue, but I don’t have the ability to single tongue "The Bartered Bride" at 144-152 or the famous "Mendelssohn Scherzo" at 90. In fact, I would offer that these tempi are out of range of the majority of players. So what do we do as performers when confronted with a fast passage that is intended to be articulated and is beyond the limits of our tonguing ability? Learning to double tongue appeared to me as a viable alternative to the old "slur-two, tongue-two" surrender.

I began experimenting with double tonguing about ten years ago. It was frustrating to discover that very few clarinetists knew how to double tongue and even fewer knew how to describe what they were doing. Robert Spring (Professor of Clarinet, Arizona State University) is probably the most renowned practitioner of clarinet double tonguing. Mr. Spring wrote a brief article on the mechanics of multiple articulation in "The Clarinet" Vol. 17 no.1 (Nov – Dec 1989). I used his article as a reference point, but I was otherwise on my own. It was not until 1998 that I began seriously practicing double tonguing and worked at developing a true fluency.

As I gained confidence in my double-tonguing I began to use it in performance. However, I soon discovered that double tonguing had a few serious drawbacks. One, I could not emulate a good staccato and two, prolonged practicing caused a change in my tongue position that altered my throat cavity. The result was a loss of focus in my sound and a tendency to play flat. I was able to play sixteenth notes at 170 to the beat, but I certainly did not like the sound. Also, most often I did not need to double tongue an entire passage, but I could not switch from single tongue to double tongue mode easily. As I practiced various excerpts it was also apparent that continuos double tonguing did not suit all metric or musical inflections.

I first stumbled on the idea of combining double tonguing with single tonguing when attempting to apply double tonguing to the "Scherzo" from Mendelssohn’s "Midsummer Night’s Dream".

The first groups of sixteenth notes do not need to be double tongued and in fact lose the separation of a good staccato when played that way. The first problem for most of us comes with bars 7 and 8. Here we have ten notes in succession, all tongued. Generally, the last three or four notes begin to sound labored as the tongue tenses. I attempted to double tongue this in the standard fashion of repetitive " t-k, t-k", but the coordination was awkward in this metric context. In order to practice without tension, I would often slur the first two notes of bar 8. It occurred to me that an insertion of a "t-k" unit instead of a slur would have the same effect of resting the tongue. Voila! It did not take me long to learn how to insert this so that it sounded quite adroit. (In this excerpt and all other examples, the "t-k" unit is marked with a bracket)

Further in the passage at bars 15 and 16 is a string of twelve notes in succession. Following the same principal, I applied the double tongue as indicated.

There are several advantages to this method. Only two notes of the twelve are articulated with a "k" and the energy of the tongue in these two places enhances the rhythmic underpinning. Also the tongue is relaxed in the ascent to "C". With relaxation one can make a feathery decrescendo which sounds very musical and virtuosic. I can easily play this excerpt at 92 and 94 is not out of range (although I think it sounds like a cartoon at that speed!) I will give a few more examples of excerpts after a thorough discussion of the basics and a method for practicing double tonguing and "Synthetic Speed Tonguing".

My method is a synthesis of double tonguing and single tonguing techniques, so you must learn how to double-tongue before you can proceed and you must have a reasonable amount of skill at rapid single tonguing. As I stated previously, this article is not meant to be a dissertation on the mechanics of articulation. The following section regarding double tonguing is not a definitive discourse, but will point in you in the proper direction for developing a concept of double tonguing as an adjunct to "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". I suggest focusing your attention on my method of speed tonguing as soon as you can incorporate double tonguing into your study. For further information on double tonguing you may wish to read Robert Spring’s article mentioned earlier.

In order to approach your study with the most success you must use a metronome. The best possible method is to use a metronome that will produce subdivisions to each pulse. I use a "DR BEAT" metronome. Hearing each subdivision (usually sixteenth pulses) as you practice will greatly enhance your ability to articulate evenly

Double Tonguing: method and practice

Double tonguing is the technique of making successive articulations by alternating the tip of the tongue against the reed with a subtle stroke of the back of the tongue against the soft palate. Unless you have learned this technique on another instrument, it will feel very foreign at first. Accept the fact that it may take a few months to become comfortable. Initially, do not spend more than fifteen minutes each day studying double tonguing. It is also important to continue to practice standard single tonguing. This will maintain your focus on good tongue position and good, clear initiation of tone.Below is the standard pattern for double tonguing where "t" represents the tongue meeting the reed and "k" represents the back of the tongue against the palate.

"In all manners of articulation the tongue may be best considered as performing the function of a valve, not as the initiator of the expulsion of air".(For single reed players this applies to the "k" stroke only. –CF)

"To make the two articulated sounds as similar as possible, the following suggestions must be followed. The vowel used with the "T" and the "K" must be the same, i.e., the "T" and the "K" must rhyme. Tone quality can be affected by changing the position of the tongue in the mouth, the same manner in which vowels are altered in speech."

"The point of articulation for the "K" must be as far forward in the mouth as is comfortably possible …. In developing the "K" attack, care must be taken to insure that the throat muscles, especially those which are involved in swallowing, are not activated at the same time the tongue is forming the "K". When this happens, the airstream is stopped not only at the "K" point, but also back in the throat. The result is one of over-riding the action of the tongue when time for the attack, and the attack will then tend to be soggy, mushy, even late."

Of course many of the problems associated with tonguing are much different for the clarinet, but Mr. Stevens makes relevant points about matching the quality of "T" and "K" when using compound tonguing and a very important point about sympathetic throat movement when producing the "K" stroke.

Apropos to Mr. Stevens’ comments, I use the consonant "t" and "k" for double tonguing. The "t" placement is the normal position for starting a tone. I use the tip of the tongue to the tip of the reed. This places the tongue in a natural position that allows the back of the tongue to touch the soft palate easily when using the "k" stroke. The vowel that produces the best results for me is "oo". Thus I think of "too" and "koo" which positions the tongue comfortably forward and is a vowel conducive to good clarinet tone.

Robert Spring uses "TEE-KEE" in order to keep the tongue high enough to produce the "k" articulation in the upper register. I have tried this, but for my taste, the sound is too thin. Also, I cannot produce the "EE" position with out a sympathetic pulling at the corners of my mouth. My concept of embouchure has always been to keep the lips "forward" and form an "oo" shape when playing. However, I do find when double-tonguing higher than "G" above the staff that a slight raising of the tongue facilitates this register.

Spring also suggests beginning the study of multiple tonguing with the mouthpiece and barrel only. I found that starting with the throat tones and a slightly softer than normal reed was also effective. He also indicates beginning at a tempo of no less than 112 with a sixteenth note subdivision. I agree that it is important to move to faster tempi early in your learning. The "k" is produced in a lighter fashion this way, but initial slow playing will help with a thorough understanding of the tongue motion and placement.

Begin with throat "E" or "F" and just try "k-k-k-k" etc. for several beats. The sound of the "k" will probably be awful when you first start - not to worry. Focus on keeping the stroke forward on the palate.

Set the metronome to 72 and using only the "k" stroke see if you can place a "k" on every beat. As you get better at this increase the metronome speed and try to lighten up the articulation. The "k" need only be a slight interruption of the air stream – similar to the slight interruption made by the tip of the tongue to the tip of the reed. You won’t master this in a few sessions, but you will become fluent enough after a few days to add the "t".

Return to a moderate tempo on the metronome (72-80). Play two eighth notes on each pulse, but as you play alternate "t" and "k".

Return to a moderate tempo (72 or slower) and play the following simple pattern.

Once you become comfortable with this, add successive groups of sixteenths to increase endurance. Return the metronome to a moderate tempo.

The final step for our purposes is to incorporate double tonguing with changing notes. This is the most difficult aspect of double tonguing and will take some time to master. The following pattern was the most useful for me in coordinating my fingers and tongue. This is also an excellent exercise for speeding up the "k" stroke. You can get inventive with this and play it through all of the keys and also apply it to the chromatic scale. Play it upwards and downwards.

Synthetic Speed Tonguing: method and practice

As stated earlier, "Synthetic Speed Tonguing" simply incorporates double tonguing technique with single tonguing. There are several advantages to this method over pure double tonguing. Only one note in four (given one quarter note subdivided by sixteenths) is affected by the "k" articulation. The tongue is in normal position for a higher percentage of time than double tonguing and produces a much better overall tone quality. Intonation is better than with pure double tonguing. When one becomes fluent with this technique it can be used quite subtly to relieve the tongue briefly in a string of notes that are single tongued. I believe this method is a much more musical approach to rapid tonguing. It can be used in areas of register, meter or musical nuance where pure double tonguing may not be appropriateTo begin, let us return to the following simple pattern, but use the "k" stroke on the second note only.

Notice again that I have added an accent to the beginning of the group. I find that starting from a rest is the most difficult aspect of using "t-k" units. The added support of air and the energy of the attack will help your start. As you develop this method you can drop the accent and think of "energized" air to support your starts. Play through all of the variations described in the section on double tonguing, but substitute the above pattern.

For example:

etc.

etc.

You already know this pattern:

Now it is time for the real thing, scale studies. The fundamental premise for my method is that the "t-k" unit can be substituted anywhere one would normally place a two-unit slur to accommodate a passage that is too fast to single-tongued in its entirety. Begin by playing only these short patterns:

Now you can extend this pattern to full scale practice. I use the following two patterns as part of my warm up routine. I play them through all keys from low "F" to "C" in the staff. If I have time I play at three tempi, 136, 144, 152. On good days I try to bump the last number up a few notches.

Once you have learned the basic concept, you can apply this method to any number of exercises. I routinely play a chromatic scale from lowest E to C above the staff and back down following the same pattern I apply to my scales. To incorporate the pattern into 3/8 or 6/8 patterns I use the "t-k" unit on the first two notes only of a six-unit group. (See example below) The scales in the beginning of Langenus Book III are in 6/8 and can be practiced in this manner.

As you move the metronome up, you will find that your upper limit for speed tonguing is the same as with your "slur-two, tongue-two" model. I cannot play as fast with the synthetic method as with a pure double tongue method, but I find the artistic and musical results to be much more satisfying.

Examples of Orchestral Excerpts

The following are only a very few examples of suitable uses of "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". I have placed brackets below or above the notes that receive the "t-k" unit.Beethoven, Symphony No. 4 – fourth movement. MM= 136 - 152

Smetena, "The Bartered Bride" – Overture. MM= 144-152

Note that at the beginning of the second system of the "Bartered Bride" I have placed a slur over the "D-B" pair of notes. It is rather difficult to start the "t-k" from this register. If the second note is clipped it will sound tongued at that tempo.

Sibelius, Symphony No. 1 – third movement

Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 3 – Second movement MM = 126 - 140

Here is another case where the ability to shift from single tonguing to a brief insertion of a "t-k" unit is possible with "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". The predominant use of the "t" renders a beautiful light quality, yet the tongue remains relaxed because of the occasional use of a "k" articulation. I do not place a "t-k" unit on the first pair of notes beginning the third system. A skip of this width from the upper register is difficult and at this point the tongue is still relaxed. I insert the "t-k" units on the next three beats only. It is difficult to play these excerpts lightly (pp) and maintain rhythmic clarity. The slight pulsing of the energized "t-k" units solves this problem.

These are only a few examples for the use of "Synthetic Speed Tonguing". There are many, many possibilities and variations and once this technique becomes a part of one’s technical vocabulary the imagination is the only limiting factor as to its applications.

Clark W Fobes

San Francisco

October, 2000